Geraldine Whittington (1931-1993), known to many as Gerri, was a notable woman of the Civil Rights Era. She left her mark on history as the first African American secretary to a U.S. President in the White House.

Gerri was born in Lothian, a historically important African American enclave in southern Anne Arundel County. As a child, she went to Lothian Elementary School, a Rosenwald school built in 1931, the year Gerri was born, to serve African American children during the period of segregation. In the 1940s, she attended Wiley H. Bates High School (now listed on the National Register of Historic Places), the only public high school available to black students in Anne Arundel County at the time. From there, Gerri went on to Virginia State College (now known as Virginia State University), historically renowned as one of the earliest, public colleges for both African American men and women in the southern United States.

Gerri left Virginia State College in 1950, where she pursued a bachelor’s degree in business administration, and promptly entered federal service with the Agency for International Development (AID) in the State Department, where she worked with Ralph Dungan. When Ralph Dungan became appointments secretary to President John F. Kennedy, Dungan invited Gerri to work with him in the White House, which she began starting in July of 1961. After JFK’s assassination in 1963, she continued to work in the White House at start of the Lyndon B. Johnson administration, at first for Walter Jenkins and William Moyers, LBJ’s closest assistants. Very quickly, they referred her secretarial services to the President.[1]

Gerri thought it was a prank when President Johnson called her to reassign her as his secretary in the White House. How do we know? LBJ taped this conversation (as he did every conversation in the White House) and we can listen to it today

She began working as LBJ's personal secretary on Christmas of 1963. Her reassignment started on Air Force Once, where she accompanied LBJ on his flight to Texas for the holiday. Right at the start of Gerri’s tenure as LBJ’s personal secretary, she finds herself walking into an all-white country club in Texas on the President’s arm, a calculated move on LBJ’s part to signal the end of segregation. In that moment, she became a prominent face of the Civil Rights Movement. The setting, at the very end of 1963, was a New Year’s Eve party at the Forty Acres Club, a faculty club for the University of Texas. The previous year, the faculty club had recently signaled its refusal to integrate by infamously turning away an African American official of the Peace Corps, which spurred on boycotting and faculty resignations in protest of the Forty Acres Club’s actions. It was a calculated move on LBJ’s part to signal his support of Civil Rights and effectively ended segregation at the club.[2]

Geraldine Whittington’s introduction to the nation as the first African American secretary to a US President was an unconventional one. On January 19, 1964, she made a guest appearance on episode #696 of the television show, What’s My Line? The game show consisted of a panel of celebrity judges that had to figure out the occupation of invited guests by deducting from the guest’s answers to 10 questions. You can actually watch Geraldine Whittington’s debut for yourself here:

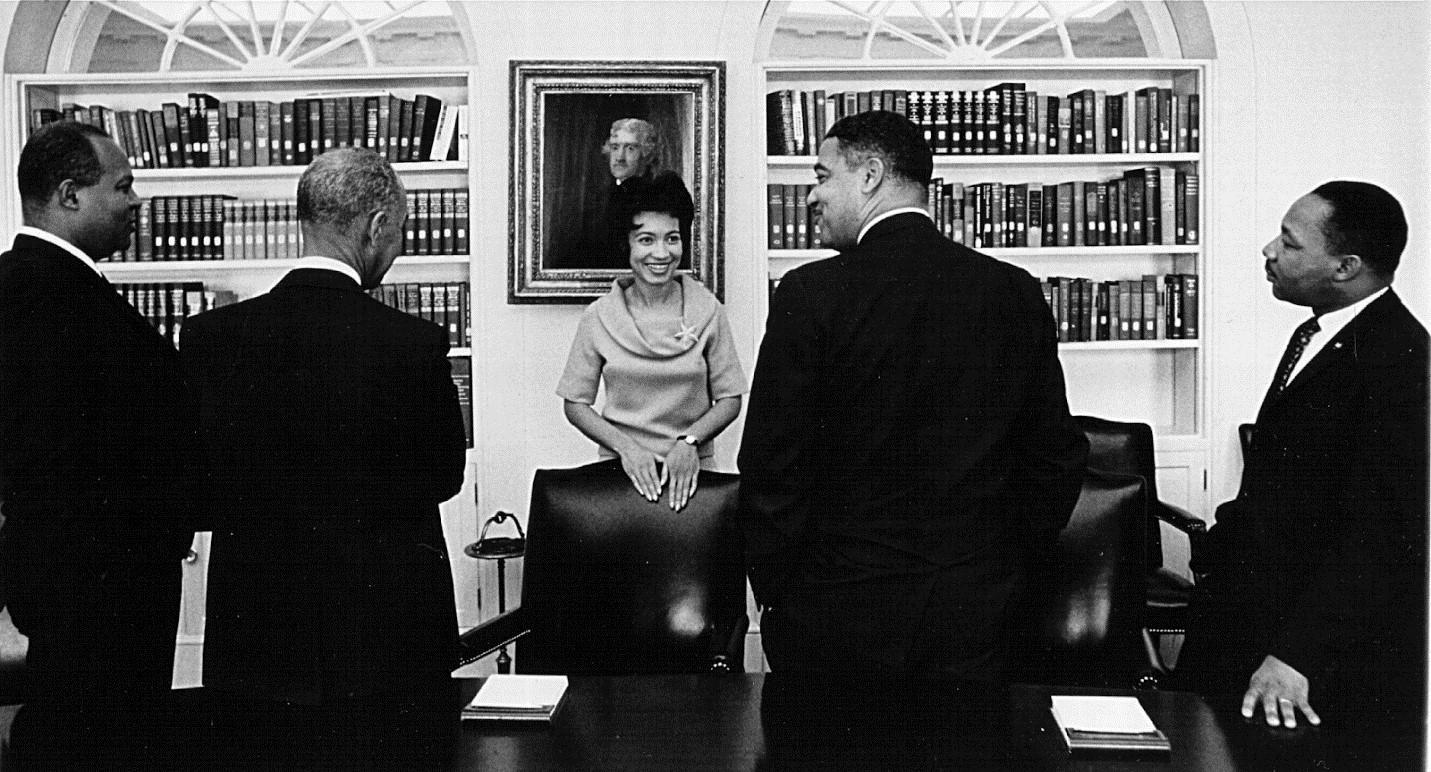

Ms. Whittington was at the heart of an administration that oversaw the passing of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, shortly followed by the Voting Rights Act of 1965, important turning points in the history of the United States. In the photograph above, you can see her chatting with Civil Rights leaders at the forefront of the movement, including Martin Luther King. Geraldine stated that the proudest moment of her career was when she was the first to learn of the appointment of the first black Supreme Court Justice, Thurgood Marshall. She would have been the first to shake his hand.[3] Gerri continued to work in the White House as LBJ’s personal secretary until the end of his term in 1969. Gerri was featured regularly in Jet and Sepia magazines as one of the success stories of the Civil Rights movement. She knew her position enabled her to represent and inspire African American women to break barriers.[4]

In February of 1969, Geraldine had to leave civil service after suffering a stroke at the young age of 38 due to cerebral thrombosis. Fighting for recovery from partial paralysis and some speech impediment, she was honored a year later at a party at the U.S. Capitol, where she was toasted by friends for her courage and for the mark she left on the White House.[5]

Geraldine Whittington continued on as a Civil Rights icon throughout her life. In 1993, at the age of 61, she lost a battle to cancer and is buried at home in southern Anne Arundel County with her mother in the cemetery of historic Mt. Zion U.M. Church in Lothian, a church that was an important epicenter of the African American congregation since the late 19th century. Gerri passed away on January 24, 1993, the same day as Thurgood Marshall.

On January 18, 1964, Geraldine Whittington stands in conversation in the White House with four prominent civil rights leaders: James Farmer, Roy Wilkins, Whitney M. Young, and Martin Luther King.

[1] https://radar.auctr.edu/islandora/object/auc.098%3A0105

[2] https://deadpresidents.tumblr.com/post/53207381610/lbjs-historic-night-out

[3] Feb 15, 1993. “LBJ’s Exec Secretary Dies: She was first to learn he named Marshall a Justice.” Jet, v. 83 (16): 56. (Source: https://books.google.com/books?id=3roDAAAAMBAJ&pg=PA56&dq=geraldine+whittington&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjPz9uMm7n2AhVBrHIEHeEQDhEQ6AF6BAgCEAI#v=onepage&q=geraldine%20whittington&f=false)

[5] May 1, 1971. “A Little Help From Friends.” The Washington Post, page E2.

Photo Credit: United States Information Agency (USIA)/Okamoto. U.S. National Archives as 306-PSA-64-268., Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Contribution by Anastasia Poulos, Archaeological Sites Planner, Anne Arundel County Preservation Planning.